Happy 100th Birthday, Julia!

I was 11 years old when The French Chef premiered on PBS. Even at that tender age, I was enthralled with food. I was already working Saturday mornings for a couple of hours at the neighborhood donut shop – a job my father had gotten for me to get me out of the house. It’s hard to believe that I was a paralyzingly-shy child back in the day. Pop knew I needed to interact with people and the donut shop was just the right place.

It seems impossible that it was 49 years ago that Julia Child first went on TV. Even more impossible that I’ve been playing with food in one way or another for 51. Impossible.

I don’t really recall wanting to be a cook. It was just something that happened. From the donut shop – where I actually ended up working for almost 6 years – to Blums, and then Pirro’s, it was the path of least resistance. I could go to school, make money on the side, eat all I wanted, and do something that came easily to me.

Even after taking the placement exams in Uncle Sam’s Yacht Club – where I actually scored high enough to get into any field I wanted – including nukes – I chose to be a Commissaryman – a Navy cook – because it took the least amount of effort. Or so I thought. I sailed through school and was assigned to an aircraft carrier. They found out I could bake and it was Bakeshop Aweigh. 12 hours a day, 7 days a week, 45 or more days in a row, I baked bread, cakes, cookies, pies. Donuts. OMG did I make donuts. About 18,000 rations of dessert in the aft bakeshop and 700 loaves of bread, 500 hamburger buns, 500 hot dog buns, and a few hundred loaves of a specialty bread in the forward bakeshop – every 24 hours. About 15 of us did that every day.

As hard as the hours were, the actual work wasn’t difficult. I spent most of my time in the forward bakeshop with the bread and rolls. At the ripe old age of 19, I had a feel for dough. I had worked for a couple of exacting task-masters and had learned well. We had a very free hand working in the bakeshop. We were required to make whatever amounts of things, and we were supposed to use the official Armed Forces Recipe Card Service recipes, but our specialty breads – and the breads and baked goods we sent to the Wardrooms – The Officers – we had more of a free hand in creating.

The military and I did not really get along very well. Although I worked hard and really did learn a lot, mentally, I was always a civilian in a uniform. A civilian who got to travel throughout Southeast Asia and eat some of the most foreign and fantastic food I had ever had.

My eyes were opened to F-O-O-D and more than just cooking, it became a fascination. I wanted to try more things, I wanted to know how things were done. My problem then as now, was I didn’t want to be taught, I wanted to experience. Hotel Restaurant School was horrible. I learned next to nothing. It was extremely difficult being at least three years older than everyone else in the class – and being a Viet Nam veteran with a full-time job and a shitty attitude. I pity some of those teachers.

But while I was hating school, I was loving cooking – and this is where Julia Child came back into play. The attitude and arrogance of some of the teachers contrasted so sharply with the attitude and openness of Julia. While the school was teaching presentation and how to impress, Julia was teaching technique and how to do it right.

For years I would read a Julia Child recipe and marvel at how she could write a three page recipe for a baguette that only had three ingredients. But she was writing her recipes in such a way that literally anyone with half a desire could create a fabulous meal. They can be intimidating, but she was about Mastering the Art of French Cooking. It wasn’t about 20-Minute Meals.

But even more important to me than the fool-proof recipes was the concept of just getting into the kitchen and cooking. She said to never apologize for what you made and to not be afraid of what you were doing. Those were concepts that I have brought with me to every job I’ve had since. At home, my mantra has been the worst thing that can happen is I throw it all out and call for pizza. I have never called for pizza, although there are more than a few things I won’t bother making again…

Julia Child first brought French cooking – authentic French cooking – to the masses in the early ’60s, but through the subsequent years – decades – she brought cooking to the masses.

She was a real person with a real passion for food. She explained the art of cooking, the techniques, and she wasn’t afraid to show the mistakes. Cooking was something real.

Today, cooking shows are about getting dropped in the dessert and cooking a meal for 300 people with yak butter in 20 minutes. I rarely watch cooking shows anymore. I love Ina Garten and a couple others, but none of these Celebrity Chefs can hold a spatula to Julia Child and none of them will ever have the impact she had on food or cooking.

She believed in doing it right and cooking with real ingredients. She believed in the pleasure of food and just didn’t worry about using real butter, real eggs, and real cream. Her emphasis was enjoying the right way to cook and eat something.

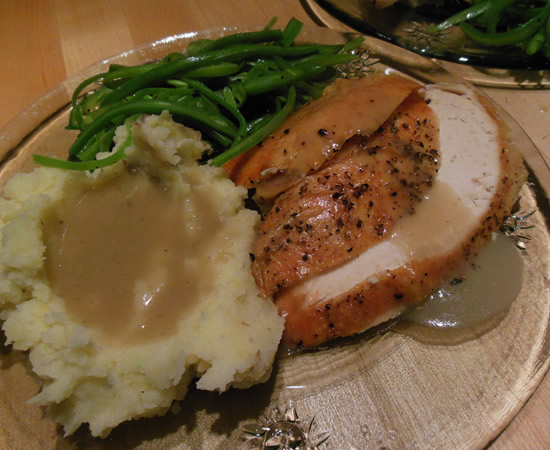

I knew I wasn’t going to be able to make a Julia Child dinner tonight, so I made mine on Monday. A simple roast chicken with mashed potatoes, gravy, and French-cut green beans – that I French-cut, myself, of course. In “Julia and Jacques Cooking at Home” she wrote “A well-roasted chicken is the mark of a fine cook.”

I didn’t follow her Poulet Roti recipe verbatim, but I did re-read it before coming up with my own version. Julia Child believed in learning through experience – and after 51 years, I’m still learning!

Here’s her recipe…

Poulet Roti

(Roast Chicken)

Adapted from Mastering the Art of French Cooking

Ingredients

- 1 3-pound whole chicken

- 3/4 teaspoon salt, divided

- 5 tablespoons butter, softened to room temperature, divided

- 1 carrot, sliced

- 1 onion, sliced

- 1 tablespoon olive oil

- 1/2 tablespoon shallot or green onion, minced

- 1 cup chicken stock or broth

Directions

Preheat oven to 425°. Sprinkle inside of chicken with 1/4 teaspoon salt and smear in 1 tablespoon butter. Truss the chicken. Dry it thoroughly with paper towels, and rub the skin with 1 tablespoon butter. Place chicken, breast side up, in a roasting pan. Strew carrot and onion around it, and set it on a middle rack of the preheated oven. Meanwhile, in a small sauce pan, melt 2 tablespoons butter and 1 tablespoon olive oil to use for basting.

Allow chicken to brown lightly for 5 minutes. Turn it on its left side, basting it with the butter and oil mixture, and allow it to brown for 5 minutes. Turn it on its right side, baste it, and allow to it to brown for 5 minutes.

Reduce oven to 350°. Leave chicken on its right side, and baste every 8 to 10 minutes, using the fat in the roasting pan when butter-and-oil mixture is empty. Halfway through estimated roasting time (when the right side of chicken is golden brown, about 40 minutes), sprinkle chicken with 1/4 teaspoon salt then turn it on its left side. Continue roasting and basting for another 20-30 minutes, until left side is golden brown. Then, sprinkle chicken with 1/4 teaspoon salt and turn the chicken, breast side up.

Continue basting and cook for another 10-20 minutes or until chicken has an internal temperature of 165°.

When done, cut and discard trussing strings, and allow chicken to rest on a hot platter for 5 to 10 minutes

Remove 2 tablespoons of fat from the pan, and discard. Then, strain the cooked vegetables and pan juices through a chinois. In a small sauce pan, combine strained pan juices and minced shallot (or green onion), and cook over low flame for 1 minute.

Add stock, and boil rapidly over high heat, scraping and discarding any white foam, until liquid reduces to 1/2 cup. Season with salt and pepper.

Turn off flame, and just before serving, swirl in 1 to 2 tablespoons of butter into the pan sauce.

Pour a spoonful of sauce over the chicken, then ladle the remaining sauce in a gravy boat for the table.